History of Dark Skies Preservation in the Big Bend

Efforts to document and preserve the dark skies in the Big Bend region of Texas span nearly a century in large part thanks to the role of McDonald Observatory, one of the world’s premier astronomical research facilities, as well the National Park Service, Texas Parks and Wildlife, local advocates, and local governments in more recent years.

1926-1939

In 1926, William J McDonald, a wealthy banker from Paris, Texas, passed away. McDonald left approximately $850,000 in his will to the University of Texas at Austin to build an astronomical research observatory, citing the lack of any such facility in the state of Texas at the time. The University of Texas partnered with the University of Chicago to select a suitable location, design, construct, and operate the new facility. The University of Chicago’s Yerkes Observatory, located in southern Wisconsin, suffered from light pollution and poor weather conditions, and thus a new observatory location was desired.

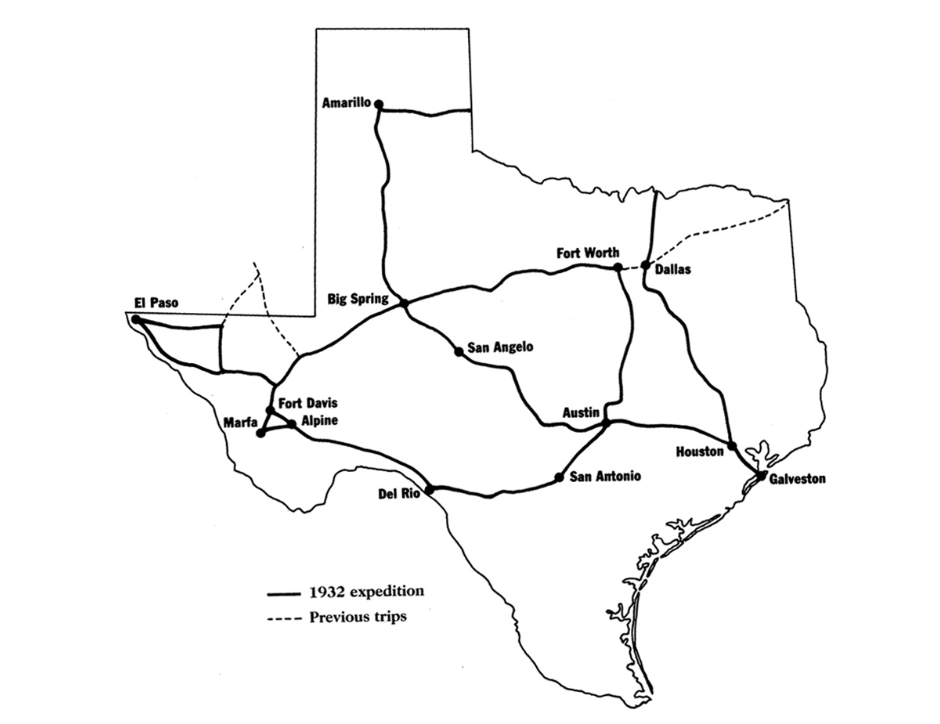

Serious investigations into site selection began in 1932 with in-person surveys across Texas. Yerkes astronomer Christian Elvey and Amherst astronomer T.G. Mehlen journeyed across Texas to scout for a suitable location, taking measurements and evaluating various sites (see map). Initial sites were proposed near Austin, El Paso, the Texas Panhandle, and other areas, but ruled out due to light pollution, unsuitable climates, and construction difficulties. They eventually settled upon a site in the Big Bend region due to the dry climate, high altitudes, and distance from major cities. They considered sites such as Hancock Hill in Alpine, Mt. Ord in Brewster County, and Mount Livermore in the Davis Mountains. They eventually decided upon “Little Flat Top” in the Davis Mountains, due to its accessible summit, excellent sky conditions, and a donation of the land from Violet Locke McIvor of the McIvor cattle ranch. The mountain would shortly later be renamed Mount Locke.

Further studies in 1937 with a then state-of-the-art photoelectric sky photometer (pictured) would confirm that the night sky above McDonald Observatory had no detectable artificial light. During this time the nearest community of Fort Davis had no streetlights, and light from other communities such as Alpine, Marfa, and Pecos were blocked by mountains or otherwise undetectable.

The 82”, or 2.1m telescope was completed and dedicated on May 5, 1939. The telescope was the second largest telescope in the world at the time and remains an active scientific research instrument today. It was later named the Otto Struve Telescope after the observatory’s first director.

1940-1974

The night sky quality above the Big Bend region remained mostly unchanged until the early 1960’s. By this point communities such as Alpine, Fort Davis, Marfa, Presidio, and Van Horn had grown in brightness enough to be noticeable, although populations remained relatively small and the area as a whole very rural in character. While the sky in the Big Bend region was still exceptionally dark, astronomers noted that many of the great observatories around the world, once thought untouchable by city lights, were increasingly threatened by light pollution. The 100” telescope at Mount Wilson in California, the largest telescope in the world for many years, was heavily impacted by light pollution from Los Angeles, and even its successor, the mighty 200” Hale telescope at Palomar Observatory, was beginning to be impacted.

In 1969, the second large telescope was completed at McDonald Observatory: the 107”, or 2.7m telescope, with support from NASA. The telescope would be used to laser range the distance to the moon using reflectors left by Apollo astronauts as well as Soviet probes, among a wide variety of other operations.

Astronomers Keith Kalinowski and Robert Roosen reviewed measurements of sky brightness made in 1960, 1972, and 1973 to confirm that McDonald Observatory remained one of the darkest observatories in the world, with natural sources of light contributing to a far greater impact on sky quality than artificial sources. However, the completion of the cutting edge 107” telescope, and spread of light pollution around other observatories, spurred conversation among astronomers, locals, and state representatives on how McDonald Observatory would preserve its exceptionally dark skies in the future.

1975-2000

In 1975, the State Legislature of Texas passed House Bill 57, the first major step towards protecting the night sky in the region. The bill allowed for any county within a 75-mile radius around McDonald Observatory to adopt regulations on outdoor lighting county-wide. Counties in Texas do not ordinarily have the authority to adopt regulations or ordinances; such power is generally limited to municipalities. In rural west Texas, however, many communities are unincorporated and many light pollution sources are not within city boundaries, so the extension to counties was viewed by many as necessary.

The first county to adopt an outdoor lighting ordinance was Jeff Davis County, home to McDonald Observatory, on November 12, 1976. At the time it was one of only a handful of places in the world to regulate outdoor lighting; the only other comparable cities were Flagstaff and Tucson, Arizona. The orders established criteria on shielding, the emission spectrum of light sources, intensity, and prohibited certain kinds of lighting such as searchlights for advertisement. Adopting these orders was not without challenges; while the ordinance allowed for a $200.00 fine as penalty of violation, enforcement was generally lax and the technical criteria were not well understood by all parties. The ordinance underwent several revisions over the years to clarify language and ease compliance.

Further support and outreach came from the Texas Star Party, an annual gathering of amateur astronomers at Prude Ranch near Fort Davis. Outreach and education, as well as the donation of compliant fixtures, was successful in ensuring Fort Davis adopted good lighting practices. Fort Davis adopted low-pressure sodium streetlighting to reduce the impact on astronomy, which was beginning to be viewed as important to the local economy and for a burgeoning tourism industry in the region.

Although communities in surrounding counties expressed some interest in dark sky preservation efforts, Jeff Davis County initially remained alone in adopting an ordinance. However, starting in the 1980’s astronomers proposed another large telescope at McDonald Observatory: the “Spectroscopic Survey Telescope” or SST. This project would evolve to eventually become the 9.2m Hobby-Eberly Telescope, the second largest in the world upon completion in 1997. The supremely sensitive telescope was also timed with a rise in tourism in the region, as visitors came to see the famed dark skies above the Big Bend region.

2000-2012

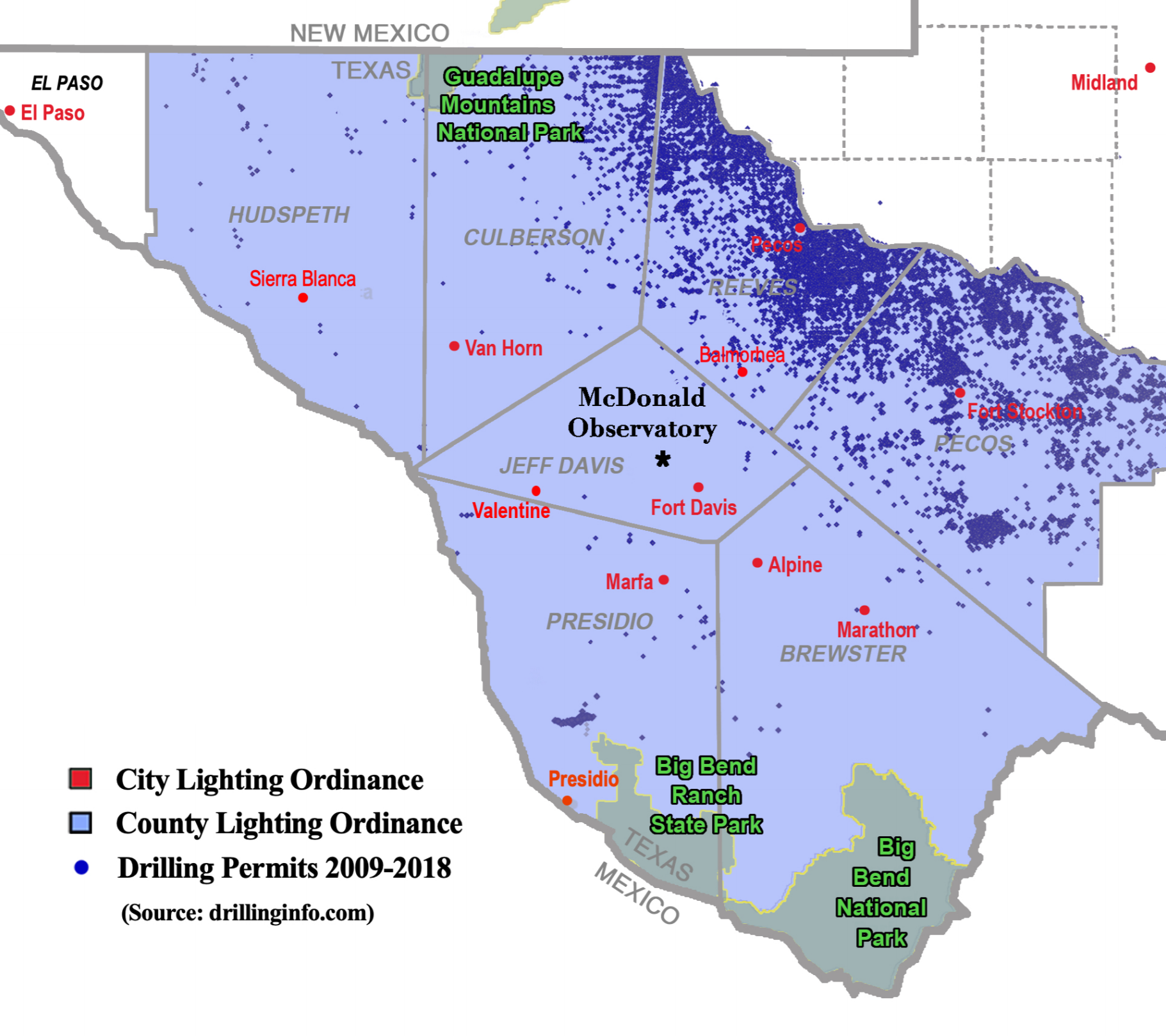

Additional counties west Texas would join in adopting orders regulating outdoor lighting in the early 2000s, starting with Hudspeth County in June 2000, followed shortly by Brewster, Presidio, Culberson and Pecos counties. These ordinances primarily required lights to be shielded, and were enforced on a complaint basis.

Reeves county was the lone holdout, citing concerns of discouraging oil and gas development in the county. However, in 2011, the state legislature updated Section 1, Chapter 229 of the local government code to require that any county, any part of which lies within 57 miles of McDonald Observatory, shall adopt orders regulating outdoor lighting. This change forced Reeves County to adopt orders, but dropped the requirement for Ward county as it was outside of the 57 mile radius.

With all seven counties and municipalities within adopting orders regulating outdoor lighting by 2012, far west Texas became the largest contiguous area in the world with laws related to light pollution (since surpassed by other areas such as the nation of Chile).

During this time, the National Park Service (NPS) began efforts to document night sky quality and begin to implement better lighting practices throughout the national park system. The NPS Natural Sounds and Night Skies division developed a sophisticated camera system to measure light pollution, called the All Sky Photometry system, which remains the current standard and adopted by McDonald Observatory for use in the region. Scientific awareness of the impact of artificial light on natural environment was beginning to grow, but remained understudied.

2013-Present

Oil and gas operations grew rapidly in west Texas from 2013-2020, peaking in intensity in 2018 in Reeves, Culberson, and Pecos counties in particular. The dramatic increase in activity resulted in a four-fold increase in light pollution seen from McDonald Observatory, and the glow from flaring and unshielded workplace lighting can still be seen as far as Big Bend National Park. While lighting ordinances were technically in place in the oilfields, they were largely unenforced and operators were unaware of them. The rapid and unchecked rise in light pollution was a wake-up call to many dark sky advocates and astronomers.

Dark skies advocate Bill Wren with McDonald Observatory worked cooperatively with industry representatives on implementing better lighting practices. Through outreach and education efforts, and cooperation with oil and gas operators and trade organizations, a set of Recommended Lighting Practices was developed for oil and gas operations. These recommended practices were endorsed by major trade organizations such as the Texas Oil and Gas Association, Permian Basin Petroleum Association, and American Petroleum Institute. The practices have aided in curtailing light pollution from the energy sector.

Between 2020-2024, many of the outdoor lighting ordinances in the region were updated to reflect changes in lighting technology, particularly LEDs, and modern understanding of light pollution as it relates to human health and the environment. These changes included limits on the color temperature of lighting and more clear language on intensity, bringing the language into the practices recommended by non-profit DarkSky International. Reeves, Brewster, Presidio, and Jeff Davis counties, and all municipalities within, adopted the new language in 2020-2021. Further support came from the National Commission of Natural Protected Areas Mexico in Mexico, which oversees the three protected lands along the border across from Big Bend. These efforts paved the way for the designation of the Greater Big Bend International Dark Sky Reserve in 2022.

In 2023, Pecos County also updated its outdoor lighting ordinance to the same language as the other counties, followed by Hudspeth County in early 2024.